I know people wanted to learn about Hitler, learn about what he was really like. So, utilizing Chat GPT-5, Gemini 3.5, and Prisma I made this story. I prompted the chats utilizing a timeline I made of research I organized over the years. This way we can use modern technology to see what Hitler life was like, rather than bits and pieces. I know that there have been many productions that covered his life, but this one is going to be more detailed. I also going to prompt Chat GPT-5 to provide phycological insight into these events.

April 20, 1889

I came into this world on a spring morning in Braunau, a small town pressed against the border of Austria and Germany. My father, Alois, was already a stern figure, and my mother, Klara, a quiet presence. The inn where I was born smelled of tobacco smoke and beer, for it was no proper home but a tavern, a lodging place where travelers gathered. My arrival was hardly noticed by the men at their tables, except for a passing remark about a child born among mugs and dice. I entered life amidst ordinary noise, as if fate hid me in common surroundings before revealing what was to come.

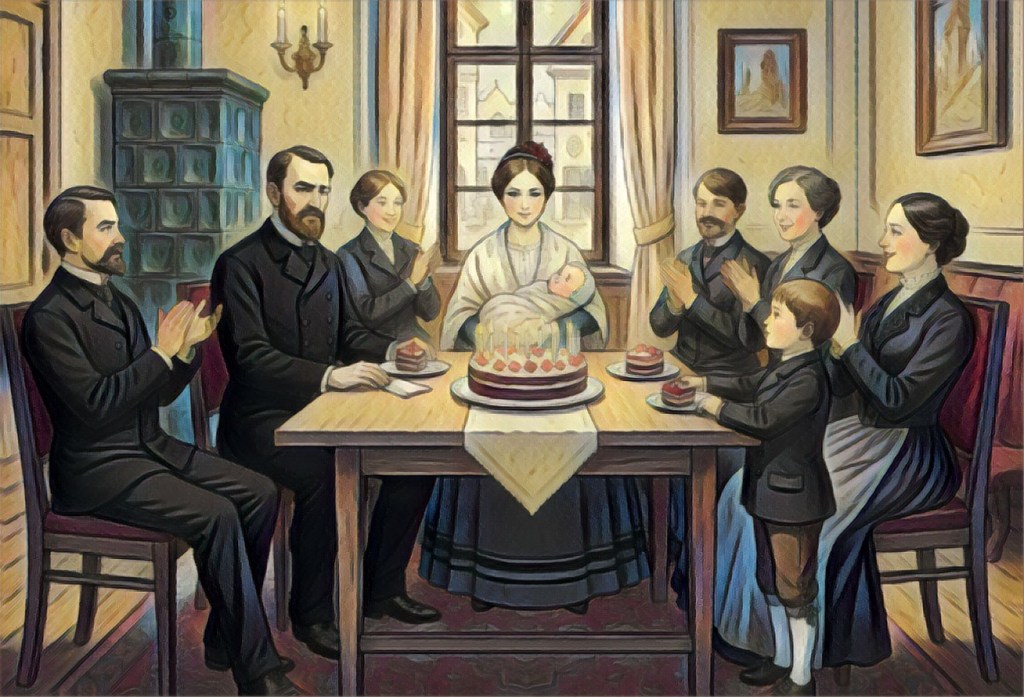

April 22, 1889

Two days after my birth, I was carried to the parish church of St. Stephan. The air was still cool, and the stone walls inside the church held a silence broken only by the priest’s voice. Water touched my forehead, and with it came the name Adolfus. My mother held me close, her face pale from the ordeal of birth, yet softened with relief. My father stood by, stern and composed, watching as the ritual was completed. The bells outside rang faintly, marking the moment, though I knew nothing of their meaning then.

1892

In my earliest years I knew little beyond the walls of our home, the streets of Passau, and the steady presence of my parents. My father, Alois, was a man of order and discipline. He carried himself with the authority of his post in the customs service, a position he guarded with pride. Each morning he departed in uniform, his stride firm, his gaze unbending. He demanded the same seriousness in the household, even of me as a child.

By 1892 he had risen further in rank, promoted once more for his persistence and knowledge of the trade routes that bound Austria and Germany together. I remember the weight of his satisfaction at that moment, though it showed itself not in celebration but in a deeper sternness. Hard work, he believed, was not to be praised-it was expected.

For me, those first three years were shaped by his discipline and my mother’s quiet devotion. She tended to me with gentleness, her presence softening the severity that otherwise filled our home. My earliest memories are of this balance: the harshness of a father who lived for his duty, and the warmth of a mother who lived for her child.

May 2, 1893

When Father’s savings at last allowed us to move into a better house, the mood within the family brightened. The new place stood more solid and spacious than the rooms we had known before, its walls clean, its windows letting in generous light. For once, Father’s stern features softened into something close to pride, as if the years of strict labor and careful saving had borne fruit.

Mother seemed lighter in spirit, arranging the rooms with care, tending to each corner so that it felt more like a true home. She looked upon me with renewed warmth, hopeful that this new beginning would bring stability to us all. Even as a child, I sensed the optimism that filled the air. The move was not merely a change of residence; it was a sign that Father’s diligence could secure a future, and that our family might rise above the modest rooms of Braunau into something greater.

March 24, 1894

Today a new cry filled our house, softer than mine but full of life-my brother, Edmund, was born. Mother’s face glowed with relief and tenderness as she held him, and Father, though never one for displays of emotion, carried himself with quiet satisfaction. For once, the usual severity in him seemed to ease, replaced by the pride of welcoming another son.

The house felt different that day-brighter, warmer, as though a new hope had entered with the child. I was still young, yet I understood enough to feel joy at no longer being alone. At last I had a brother, someone to share the days with, someone to walk beside as we grew. The sound of Edmund’s small cries promised companionship, and the whole family seemed lifted by his arrival.

April 1, 1894

Father returned home today with news of a change in his work. He had been transferred to a new post in the customs service, one that demanded longer hours and stricter attention to regulations. From him, I saw the weight of duty etched into his face, the quiet strain that came from enforcing rules along the border, checking papers, and watching travelers with constant vigilance.

His work defined him more than any other part of life. The discipline it required hardened him, shaping his manner and the expectations he held for us at home. Even in moments of rest, he carried the precision and order of his job in every step, every glance. Yet there was pride too-a sense that his labor mattered, that he upheld law and authority. For me, those first years were marked by the rhythm of his work and its effect on our household: the steady presence of a father who demanded respect, the sharp edges of his temper softened only by Mother’s patience, and the knowledge that effort and duty were never separate from life itself.

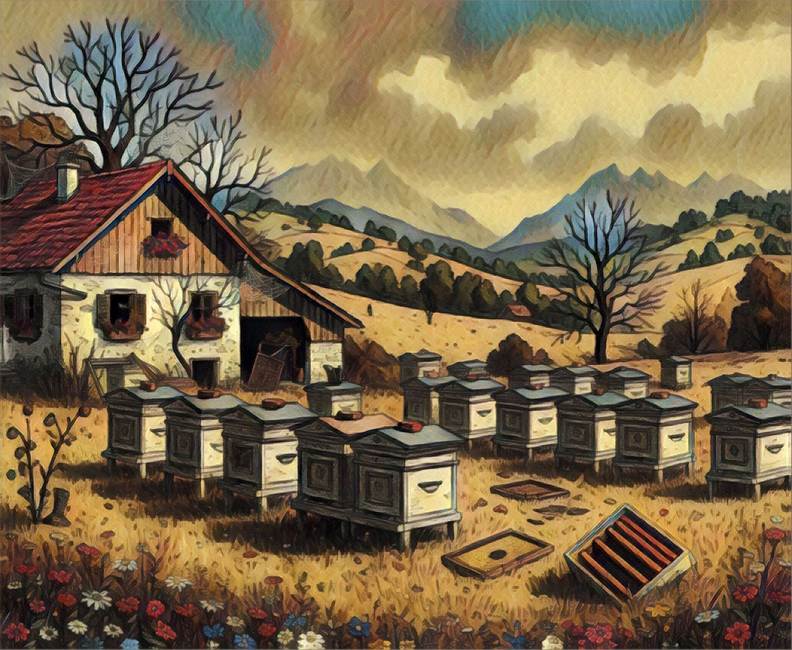

February, 1895

Father has taken a new path. He retired from his post in the customs service and purchased a small property in Hafeld to begin a beekeeping farm. It is a strange, unfamiliar venture for him, far removed from the rigid order of his previous work. I hear he studies the hives carefully, tending to the bees with patience and precision, as though the tiny creatures require the same discipline he demanded in his office.

The move has taken him physically away from the family for stretches of time, leaving Mother to manage the household alone with us children. Though I miss his presence, there is a quiet excitement in the change-a sense that Father is exploring something new, something that allows him a different measure of control and accomplishment. For the first time, the family feels the distance of his work not as strictness, but as an experiment in life, a venture into the unknown that might bring prosperity in ways his former office never could.

April, 1895

At last, the family joined Father at the bee farm in Hafeld. The house was small but sturdy, surrounded by fields and the hum of countless hives. Mother busied herself arranging our new home, and even the work of moving seemed lighter with the promise of fresh air and open space.

Father’s presence here was different-less rigid, yet still filled with the quiet discipline of a man tending his livelihood. I watched him among the hives, careful and deliberate, as though each bee required the same precision he once demanded of his duties at the customs office. The landscape was new to me, full of paths and trees to explore, the scent of flowers drifting on the wind. For the first time, our family life felt intertwined with nature and labor, a daily rhythm shaped not by offices or regulations, but by the bees and the seasons themselves.

May, 1895

I began school in Fischlham today, a long walk from the farm that left my legs tired before I even reached the classroom. The teachers spoke in measured tones, repeating lessons I already felt I could understand, yet the exercises felt endless and without purpose. I could not see the point of memorizing rules and facts when the world outside the windows held so much more to discover.

All I wanted was to be home, where my pencils and paper waited. Drawing filled me with a quiet joy that school could not offer-a chance to shape what I imagined, to capture scenes as I saw them, rather than memorize what someone else deemed important. The hours dragged on, and with each passing lesson, I felt a stronger longing for the farm, the fields, and the quiet of my own thoughts.

June, 1895

Father has fully retired now and spends nearly all his days at home. At first, I thought it might bring comfort, a chance to be closer to him, but it has only made the house heavier. His presence is constant, his eyes always watching, his patience thinning with each passing hour.

He has grown harsher, especially since learning of my disinterest in school. The teachers’ rules mean little to me, yet he interprets my lack of enthusiasm as defiance. His anger flares quickly now, sharp words cutting across the quiet of our home. Even Mother’s gentle hand seems unable to soften him as it once did. I feel the weight of his judgment every day, and the farm, which once held promise of calm and nature, has become a place of strictness and unease.

Fall 1895

Father’s venture with the bee farm has failed. The hives did not produce as he had hoped, the crops were unreliable, and the work demanded more than it returned. I watched him move among the empty frames, a quiet frustration growing in his eyes. He spoke less now, and when he did, it was sharp, bitter, a reflection of disappointment he could not keep contained.

The house feels heavier still, burdened by the weight of failure. Mother tries to smooth over the tension, but even her warmth cannot mask the strain that fills every room. I sense that Father’s pride has been wounded, and with it, his temper has grown darker. Life on the farm, once a promise of a new beginning, now feels like a reminder that even effort and discipline cannot guarantee success.

Winter 1895/96

Father has left the farm to pursue an education in the hotel business, a decision that unsettles the household more than I expected. He departs early each day, leaving Mother to manage the home and care for us children almost entirely alone. The house feels emptier, quieter, yet heavier in a strange way-as if his absence casts a shadow rather than relief.

I do not fully understand his choice, only that he seeks a new path, one that pulls him far from the work and family that once defined him. His letters speak of study and discipline, of learning to manage rooms, guests, and orders, yet there is a distance in them I cannot bridge. I long for the old days on the farm, when at least the work was tangible, and the hum of bees offered something to watch and understand. Now, the rhythm of our lives has changed, leaving a sense of uncertainty and longing that settles over us each evening.

January 21, 1896

Today, Mother gave birth to Paula, yet Father was absent, away pursuing his hotel training once more. I watched as Mother held the new child, her face pale but serene, and I felt a quiet anger swell inside me. Father’s decisions are meant to secure wealth and position, yet in doing so, he removes himself from the family entirely, leaving us to endure the trials of life without his presence.

I cannot understand why the promise of money and status matters more than the small, pressing needs of those who depend on him. Even as a child, I feel the injustice: a home divided, a father chasing opportunity while his children and wife labor under his absence. I wish he could see what it costs to gain for himself while leaving us behind. The joy of a new sibling is dimmed by the hollow absence of a father who chooses ambition over presence.

1896-1899

These years have been marked by constant movement, the house no longer a stable place to call home. Father’s ventures, always promised as new opportunities, have carried us from one town to the next, each move an attempt at profit or success that rarely lasts. One year we are in Hafeld tending the failed bee farm; the next, we are somewhere else, Father pursuing a business he believes will bring wealth or prestige. Each relocation leaves behind friends, neighbors, and the small comforts of familiarity, replacing them with the strange faces and customs of another town.

For me, school has been a constant trial. Every new place demands a fresh start: new teachers, new rules, new lessons. Classrooms blur together, and lessons are repeated as though the prior instruction meant nothing. I have had no chance to grow accustomed to any one school, to form bonds with classmates, or to find a rhythm in my studies. I long for the hours I could spend drawing at home, yet there is little time or stability for such pursuits.

The family bears the strain differently. Mother moves tirelessly to settle each new house, her quiet strength holding us together. Paula and Edmund are young and largely unaware of the chaos, but I feel it acutely. Father’s absence is inconsistent-he is sometimes here, sometimes gone-but always his presence carries authority and tension. His pursuits are meant to improve our standing, yet each failure leaves him more impatient, more strict, more critical of any perceived laziness or disinterest, especially mine.

By the end of these years, I have learned the rhythm of uprooting, the unease of new surroundings, and the frustration of never being able to settle. The world outside feels vast and unyielding, yet home offers little comfort, shaped by Father’s ambitions and the constant search for success that seems always just out of reach. I cling to small things-drawing, observation, the quiet moments with Mother-but even these are fragile in a life so unsettled.

February 2, 1900

Today, the light of my earliest years has been extinguished. Edmund is gone. My brother, my companion in childhood, was taken by illness before he had the chance to grow into the world. I do not know how to name the emptiness this leaves inside me. For so long, I had believed that having a brother meant I would never be alone, that the days of play, exploration, and quiet companionship would stretch endlessly before us. All of that hope, all of that imagined future, has vanished in a single cruel moment.

I feel a hollow ache that settles deep in my chest, a weight that no comfort can lift. Mother weeps silently, holding the small, fragile body of the brother I will never hear laugh again. Father is silent, his eyes sharp and cold as always, but I sense a tension in him as if the failure of the world to preserve life reflects on him as well. I am left with a storm of grief I do not know how to weather.

The house, once alive with the small sounds of children and the rhythm of family, feels impossibly empty. Even the farm, the fields, and the distant hum of the bees seem muted, as if the world itself mourns with me. I am consumed by sorrow, by anger, by the sharp awareness of fragility, and I realize for the first time that life can end without warning, leaving those left behind to carry the unbearable weight of absence. In this loss, I understand the fragility of hope, and the sharp cruelty of reality.

May, 1900

School has grown into a strange mix of challenges and fascination. The lessons are difficult, demanding patience and attention that often leaves me exhausted, yet there is satisfaction in understanding something new, in seeing a concept take shape in my mind. I feel that, in these moments, I am stretching beyond what I know, even if the days are long and tiring.

At the same time, I have begun to devote more of myself to drawing. Art has become my refuge, a way to escape from the rigid structure of school and the constant demands at home. With pencil and paper, I can shape the world as I wish, capture its details, and give form to what I imagine. Each sketch, each careful line, feels like a small triumph, a private space where nothing -neither strict teachers nor Father’s harshness -can reach me.

Even as school grows more draining, I have discovered that there is a balance, however delicate, between discipline and creation. The world outside often feels constrained, yet on the page I find freedom. Drawing has become more than a pastime-it is a companion, a place to breathe, and a reminder that there is something I can shape and control in a life otherwise filled with uncertainty.

Sep 17, 1900

We have come to Linz. Father declared it was necessary, that in the city there are greater opportunities, stricter teachers, and the proper discipline I so clearly lack. He spoke as if it were all settled, and so it was. Our house feels smaller than Braunau, though the city itself towers around me, loud and restless.

The new school is far larger than anything I have known. The halls echo with voices, with footsteps. There are so many boys, some already seeming like men. I feel myself swallowed among them, a face without distinction, just another child to be judged and measured. The lessons are harder, more exacting, and the masters expect more than I ever imagined possible. I spend hours staring at the pages, my mind wandering to other things, only to be scolded for not keeping pace.

Yet Father insists this is for my own good. He says a man cannot amount to anything without the sharp edge of education. He is determined I must not drift into mediocrity. But he does not see how heavy this burden feels. Each morning I step into the school with dread, knowing the trials to come, and each evening I leave with a weariness that presses down upon me.

Still, I try to believe there is som e sense to it, that enduring this will prove me capable. Though often I wonder if Father seeks to mold me into something I cannot be.

1901

The results from school came. Failure. In both mathematics and physics. Two stones that have weighed upon me from the beginning, dragging me into the depths where no air remains. I told myself that I might endure them, that somehow by effort or fortune I could overcome. But no-today they have crushed me.

Father’s rage was as fierce as I had feared. His voice struck harder than any cane. He shouted of my laziness, my lack of discipline, my foolishness. He said I would never be anything, that without these subjects I was doomed to the same mediocrity he despises in others. The more he spoke, the more I felt the walls press upon me. His disappointment is heavier than my own.

And yet, I cannot help but think it was a mistake-not merely mine, but a mistake of life itself. Why must my worth be measured by these numbers, these cold problems that mean nothing to my heart? I am not meant for them. My mind does not move along their rigid paths. I see pictures, forms, buildings, faces. I feel something stir when I think of art, of history, of the great men of the past. But to Father, these are worthless dreams.

Still, I wonder-if only I had endured more, tried harder, perhaps he would not despise me so. Perhaps I would not despise myself so.

1902

I have managed to pass my classes this year, though it feels like a hollow victory. Father should be pleased, but instead he has grown even more severe, not only with me but with Mother and Paula as well. His temper, once sharp but measured, now breaks loose more often, like a whip striking at anything in reach. His voice carries through

It seems the bottle has taken more and more of his hours. He drinks in the evenings, and then the shouting begins: harsh words about wasted time, about my lack of discipline, about Mother’s softness, about Paula’s noise. Even when he falls quiet, the house feels uneasy, as though everyone is waiting for the next outburst.

I once thought that passing my studies might give me some relief, that perhaps he would ease his grip if I proved myself capable. But the truth is crueler: my effort buys me nothing but further demands, higher expectations, harsher punishment. The more I do, the less it seems to matter.

In the midst of this, I find I no longer draw as I once did. My little sketches, the hours bent over paper-these used to carry me away into another world. Now I feel too drained, too restless, too watched. The pencil lies idle, the paper blank. What was once a refuge is slipping from me.

I had hoped that school might one day lead me toward something brighter, but all I feel now is exhaustion. I pass, yes-but what good is it, when life at home grows darker by the day?

1903

The night outside pressed against the windows, the countryside silent except for the wind. Inside, the farmhouse felt colder than the frost. The only sounds were the coughs in the shadows and the relentless ticking of the clock on the wall.

My father sat at the table; his figure carved in stern lines by the dim lamplight. His voice filled the room-sharp, commanding, inescapable. Orders barked, one after another, leaving no space for thought, no room for softness.

We sat stiff, my siblings and I, bound by his presence. Every word carried weight, every glance a warning. I listened in silence, the air heavy in my chest, the walls closing in.

The darkness outside felt freer than the room we sat in.

January 1903

The tavern smelled of smoke and spilled beer, voices rising and falling around us. My father spoke with his usual force, words striking like hammers against the table. Then suddenly his voice broke off.

A crash of glass, the scrape of chairs, shouts splitting the air. I froze, watching him fall, the noise around me spinning into chaos.

And then-silence. The scene dissolved, replaced by the toll of funeral bells. Cold and distant, they rang not with sorrow, but with finality. I did not cry. I only listened, stunned, as the world carried on without him.

February 1903

The day of the funeral was gray, the sky hanging low over the churchyard. The air smelled of damp earth and smoke from the chimneys. People stood in black coats, whispering, their eyes cast down, their breaths visible in the cold.

The coffin lay before us, heavy, immovable, as though even in death my father refused to yield. The priest spoke, his words echoing without warmth, just another duty performed. Bells tolled above us, each strike a reminder that something had ended-though I wasn’t sure what it meant for me.

I did not weep. The others did, their grief spilling freely, but I kept my face still. Inside, there was only shock-an emptiness I could not name. I watched the earth cover him, the sound of shovels striking the soil sharp in the silence.

When it was done, we turned away, leaving him there in the cold ground. The world did not pause; it never does.

Father is gone now, buried and silent. The house feels emptied of his voice, that booming presence that once filled every corner. I mourn him, yes, for he was still my father, and I wish we had known one another differently. I wish his hand had guided instead of struck, that his words had built me up rather than ground me down. But such things are beyond reach now.

In truth, beneath the grief, I feel a strange sense of release. His endless demands, his temper, his suspicion of everything I loved-they are finished. For the first time in my life, I do not brace myself for his footsteps, his rebuke, his heavy hand. The air is lighter without him.

And so my mind turns to what has always given me joy: art. I can now take up the pencil without fear of hearing his scorn. I can spend my hours sketching without the shadow of his disapproval hanging over me. Perhaps, at last, I can devote myself fully to drawing, to the visions in my head, and not to the path he forced upon me.

It is a sad thing to admit, that a son can only find freedom in a father’s absence. Yet that is the truth I feel. In his death, I see a door opening-a chance to live for myself, and for the images I long to bring to life on paper, with a pencil and paint brush. This closes one chapter of my life, marked by his voice, his rules, and his punishments. What comes next, I hope, will be a career of my own, as a world class artist.